Inside the Core, Core III Class Reads C. S. Lewis Book

Thursday, October 12, 2023

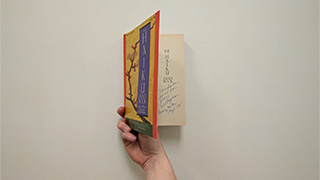

Inside the Core, my own Core III class, "Fantasy and Faith: Tolkien and Lewis and

their Precursors" (cross-listed as an upper-level English elective), is reading C.

S. Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. Today we discussed how the story, though largely set in a magical place in Narnia,

actually relates well to many of the horrors being experienced in the world today.

In keeping with Core III’s purpose of "Engaging the World," we looked at some connections

between this text and what is happening in the world today.

Inside the Core, my own Core III class, "Fantasy and Faith: Tolkien and Lewis and

their Precursors" (cross-listed as an upper-level English elective), is reading C.

S. Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. Today we discussed how the story, though largely set in a magical place in Narnia,

actually relates well to many of the horrors being experienced in the world today.

In keeping with Core III’s purpose of "Engaging the World," we looked at some connections

between this text and what is happening in the world today.

Like now, with the newly erupting war in the Middle East coupled with the ongoing war in Ukraine, the setting of Lewis’ first fantasy in the seven-book Narnia series is a period of warfare. It is World War II, and four children (Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy) are sent out of London to keep them safe, to the house of an elderly professor. This situation is based on historical reality as during the blitz, British children were, in fact, sent out of London, where their parents remained, so they would not be subject to the intense bombardment of Britain by the Nazis. C. S. Lewis and his brother, Warnie, hosted several children during the war at their home, the Kilns, on the outskirts of Oxford. It is in this already frightening situation that the children find themselves entering another world through a magical wardrobe.

We talked a bit about how sometimes it is easier, particularly for children for whom this book was intended but, I would argue, for most of us, to face terrible things thought the lens of fantasy. Bruno Bettelheim argues this point in his famous book The Uses of Enchantment. Children already know evil exists in our world; fantasy such as fairy tales and other mythical stories takes them to a place where, through make-believe, they can face some of the things they fear in our world. J. R. R. Tolkien makes a related point in his famous essay "On Fairy Stories" about how fairy tales and other fantasies can help us engage with the real world:

But in God's kingdom the presence of the greatest does not depress the small. Redeemed Man is still man. Story, fantasy, still go on, and should go on. The Evangelium has not abrogated legends; it has hallowed them, especially the "happy ending." The Christian has still to work, with mind as well as body, to suffer, hope, and die; but he may now perceive that all his bents and faculties have a purpose, which can be redeemed. So great is the bounty with which he has been treated that he may now, perhaps, fairly dare to guess that in Fantasy he may actually assist in the effoliation and multiple enrichment of creation. All tales may come true; and yet, at the last, redeemed, they may be as like and as unlike the forms. (15)

He goes on to explain that a key element in any fairy story is eucatastrophe, the good catastrophe, where a great potential evil is faced after it is almost successful in destroying a world, a group, or perhaps just an individual protagonist, but the evil is averted by "the miraculous, joyous turn."

In The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, two eucatastrophes occur. The first involves Edmund, one of the four children who

get into Narnia through a magical wardrobe. The least likable of the group, Edmund

mocks Lucy, who gets into Narnia first, but when he goes there himself, following

her, he meets the White Witch, who tempts him with enchanted Turkish Delight, getting

him to give her information about his family and eventually betraying them to her.

His sin causes him to be subject to death at the Witch’s hands because, as she puts

it, all traitors belong to her. However, Aslan, the great Lion (who in this "supposal,"

as Lewis called the story, instead of an allegory, is the incarnation of God in Lion

form), agrees to die in Edmund’s place. His redemption of Edmund is a eucatastrophe,

small in scope in that it helps mainly one person, but much larger in implication

in that Edmund represents all of us. The second eucatastrophe is the larger one, in

which Aslan and his followers completely overthrow the White Witch, and the four children

are crowned "kings and queens of Narnia" on four thrones in Cair Paravel, their castle.

In The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, two eucatastrophes occur. The first involves Edmund, one of the four children who

get into Narnia through a magical wardrobe. The least likable of the group, Edmund

mocks Lucy, who gets into Narnia first, but when he goes there himself, following

her, he meets the White Witch, who tempts him with enchanted Turkish Delight, getting

him to give her information about his family and eventually betraying them to her.

His sin causes him to be subject to death at the Witch’s hands because, as she puts

it, all traitors belong to her. However, Aslan, the great Lion (who in this "supposal,"

as Lewis called the story, instead of an allegory, is the incarnation of God in Lion

form), agrees to die in Edmund’s place. His redemption of Edmund is a eucatastrophe,

small in scope in that it helps mainly one person, but much larger in implication

in that Edmund represents all of us. The second eucatastrophe is the larger one, in

which Aslan and his followers completely overthrow the White Witch, and the four children

are crowned "kings and queens of Narnia" on four thrones in Cair Paravel, their castle.

The ending shows the triumph of good over evil, of mercy over judgment. Though the children return from Narnia to a world where World War II is still raging, they are now stronger, more resilient, and perhaps even wiser than they were when they entered the wardrobe. Fantasy can do the same for us, lifting us out of this world in order to see it better (and hopefully engage with it more meaningfully, morally, and charitably) for having been to another world in literature.

Categories: Arts and Culture, Education