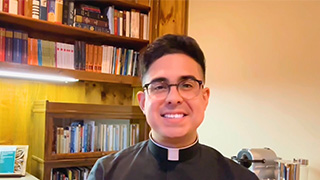

Inside the Core, We Welcomed Chris Bellitto, Ph.D.

Thursday, October 5, 2023

Prof. Chris Bellitto, Ph.D., Historian

Inside the Core this week we heard a lecture, sponsored by the Catholic Studies Department and co-sponsored by the University Core, by Christopher Bellitto, Ph.D. history professor at Kean University, talking about "Humility: the Secret of a Lost Virtue." The talk fits in very well with the text many Journey classes are reading around this time, the Gospel of Luke. Bellitto, who is a medievalist and serves as overseeing editor of Brill's Companions to the Christian Tradition and Academic Editor-at-Large for Paulist Press, believes this virtue is crucially important and one whose relevance our world desperately needs to recover. Click here for more information about Bellitto and his talk.

Bellitto made several points about humility. For one, humility is not putting oneself down; rather, it is realizing that one is not God, but a creature, albeit a good creation, but one that is not sufficient in itself. We all need God and one another. Bellitto feels this virtue, though never easy for human creatures, became increasingly out of favor as we moved from the medieval world to the modern one. He spoke about how people today tend to label others and then, without trying at all to empathize or listen to their point of view, simply write them off. While humility is the opposite of arrogance and power-grabbing, it is not weak, nor is it overly self-effacing. In fact, Bellitto argued too much (false) humility can be a form of pride. But truly humble people can have legitimate pride in a job well done, for example, and acknowledge their own gifts, but acknowledge they are not the source of their personal attributes, nor their own existence. The virtue is important in both Jewish and Islamic traditions as well, in both involving a submission to God and a just respect (biblically called "fear of the Lord") for God.

The Salutation (of Mary by Elizabeth in Luke 1) by Evelyn de Morgan, 1883

So, how does this connect with the Gospel of Luke? Of all the Gospels, this one is said to focus on the servant nature of Jesus. The symbol of Luke’s Gospel is an ox, a humble beast of burden. Luke’s Gospel is the only one to include Mary’s beautiful prayer of praise when she visits Elizabeth, the Magnificat, in which she says, "My soul exalts the Lord, and my spirit has rejoiced in God my Savior. For He has had regard for the humble state of His bondslave" (Luke 1: 46-48). She goes on to say later in the prayer, "He has scattered those who were proud in the [ak]thoughts of their heart. He has brought down rulers from their thrones and has exalted those who were humble. He has filled the hungry with good things and sent away the rich empty-handed" (Luke 1: 51-52). Luke’s Gospel tells about the humble shepherds coming at the birth of Jesus and how Mary and Joseph gave the sacrifice allowed for poor people when presenting Jesus at the temple (both stories in Luke 2).

Luke tells the story of Jesus and his disciples being prevented from entering a Samaritan town because they were heading toward Jerusalem (being Jews, whereas the Samaritans did not worship in Jerusalem, a point of contention). When James and John wanted to call fire down from heaven upon the unwelcoming town, Jesus merely "turned and rebuked them, and said, ‘You do not know what kind of spirit you are of; for the Son of Man did not come to destroy men’s lives, but to save them.’ And they went on to another village" (Luke 9:54-56). And if this patient and non-vengeful reaction of Jesus to the Samaritans is not enough to illustrate the virtue of humility, his choosing to make a Samaritan the hero of the parable told in the next chapter (Luke 10: 30-37) certainly shows Jesus’ willingness not only to forgive but his willingness to show someone from a group considered likely even by some of his disciples as enemies as a role model for his Jewish audience is remarkable. Humility, as Bellitto said, shows itself in seeing "the other" as another human on the same journey as ourselves, not someone or, worse, something to despise and to reject.

Christ and the Good Thief, by Titian, 1566

Finally, as Jesus approaches his death, Jesus’ humility is most clearly seen. On the way to Jerusalem, his disciples argue about "who is the greatest." His response offers a clear and powerful definition of humility: "The kings of the Gentiles lord it over them; and those who have authority over them are called ‘Benefactors.’ But it is not this way with you, but the one who is the greatest among you must become like the youngest, and the leader like the servant. For who is greater, the one who reclines at the table or the one who serves? Is it not the one who reclines at the table? But I am among you as the one who serves" (Luke 22:24-27). This story is in Matthew’s Gospel as well, but the account of Jesus’ encounter with "the good thief" on the cross is in Luke’s Gospel only. Here, put to death between two criminals, Jesus humbly and gently encounters the one who acknowledges his own sins and then asks "Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom." In a moment of great mercy, Jesus promises the man, Luke 29: 39-43).

Humility is best expressed not in words that draw attention to it, but to actions, like those depicted by Jesus in the Gospel of Luke. If humility is a lost virtue or one on the way to being lost, studying this great Core text may help us to restore its value, meaning, and purpose.

Categories: Faith and Service, Research